The Pelvic Health Collaborative invited me to present a lecture about the importance of talking about sex with patients. I passionately believe it should be an integral part of an evaluation of an individuals’ overall health and well-being. Any discussion with adult patients tends to be site/disease specific, i.e., after prostate surgery or heart attack. But what about patients with Crohn’s disease, arthritis, anxiety or obesity that are not considered directly related to sex? Are we asking these patients about their sex lives? We need to be. Because everything can affect sex and sex can affect everything.

An article was published in the New York Times entitled “When Did Porn Become Sex Ed?” Kids are not talking to their parents, their friends, or their doctors, so they turn to the Internet. The access is so easy and anonymous – straight from the smart phone. This is where they are learning how it is done. Is it any wonder performance anxiety is on the rise? What happens to expectations after watching internet porn? While some strides were made during the last administration in promoting comprehensive sex education, it was removed from the 2018 federal budget.

Average length of time for conversations between

physicians and adolescents about sex = 36 seconds.

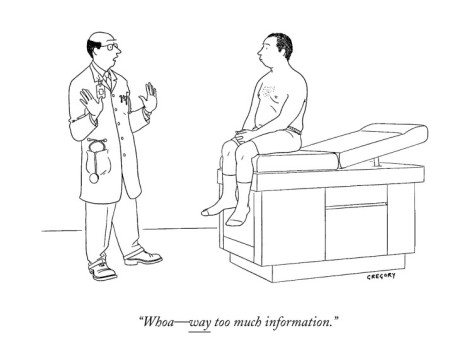

OK, parents I can understand (who ever willingly talked to their parents about this stuff?) but it should be easier to talk to the doctor. Most doctors don’t ask the questions, despite the fact that surveys show that patients want to talk to their doctors.

So, why aren’t doctors doing their job

and asking the right questions?

The main reason doctors aren’t asking, is because they aren’t always sure what to do with the answers! There is a fear of opening Pandora’s Box. Average medical school training about sex is about 8 hours in 4 years, a pathetically short amount of time for such an important health-related topic. There also may be a fear of offending the patient or an underlying fear of being accused of sexual misconduct. Generational obstacles may play a part, assuming someone is too old or too young to be having sex. Doctors in one speciality may feel it is another doctor’s problem. In a patient with multiple medical issues, it just may not be considered a priority. That may indeed be the case, after surgery or while being treated for a serious illness. But, at some point it should be brought up as the procedure (surgery, childbirth, etc), treatment, medications or illness itself may, and very likely will, have a profound impact on the patient’s sexuality.

1/3 of young and middle-aged women and 1/2 of older women experience some type of sexual problem such as low desire, pain during intercourse or lack of pleasure. The numbers for men are similar. In fact, one of the biggest changes we have seen in recent years is the increase in desire disorders in men. Hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) is the most common sexual disorder for both men and women. Addy (flibanserin) is the first FDA approved drug to treat HSDD in women but its benefits are debatable and its sales have been justifiably lackluster. In my practice, we conducted a clinical trial of a potential HSDD treatment, with a medication given on an “as needed” basis but data from that study has not been published. Intrarosa (Prasterone), approved for pain during intercourse (dyspareunia) in postmenopausal women, has been a game changer for many women yet a stunning number of physicians are not even aware of it. Clearly more options for treatment are needed for both men and women.

Just as we inquire about sleep, appetite, fever and pain, we have to ask about sex. It is on us to see the whole patient and to be able to talk about what can be the elephant in the room. Even though we are not trained. We need a revolution in the culture of health care to bring this subject out in the open.

Thank God for Porn. There is VR porn already.Robots and sexdolls are coming up with attendant moralproblems because they will be very sofisticated

Doesn’t take away doctor’s responsibility to include sex in basic health assessment

Of course. Just defending porn and

mentioned one future problem. Another is with androids and animation will the law be precluded from condemnation of even violent and kiddie porn. The medical profession has always followed the culture and then followed with a “desease”, same sex relations were mental I’ll mid in the DSM but not now.

I have nothing against porn, it just shouldn’t be used in lieu of sex ed

Why would physisians have the responsibility of teaching sex Ed? The movies are so much more accurate.they even use hats! Who does that anymore? I’m sure my kids and grandkids appreciate the storck. I like the movies and those in the oldest profession

In addition to being 65 and way post menopausal and therefore depleted of hormones, I have a medical condition(trigeminal neuralgia) and take a boatload of anti-seizure meds that have seriously depressed my desire. any suggestions?

Your first goal would be to try to minimize the use of all pharmaceuticals in collaboration with a smart and caring neurologist. Any other route to pain management should be explored- Topicals like menthal, capsacin or diclofenac may be efficacious without side effects. Acupuncture or regional nerve blocks are also options. Explain that sexual heath is important to you and needs to be considered in your treatment plan.

Remember DHEA as an option for post menopausal dryness.